Why is there a statue of a diver inside Winchester Cathedral? Why is there a pub named The William Walker facing the Cathedral? The answer to both these questions lies in the extraordinary assignment undertaken between 1906 and 1911 by a man who died one hundred years ago this month – an assignment which is particularly well recorded in the Winchester Cathedral Archive, held at Hampshire Record Office, and which is featured in a display now on show in the Cathedral (until 31st October 2018).

William Walker in his diving suit, Hampshire Record Office: HPP5/1/32.

The land on which the Normans began to build the Cathedral in 1079, alongside (and eventually overlapping the site of) its Anglo-Saxon predecessor, was not ideal geologically. The site was on the prehistoric bed of the Itchen (which had been diverted to the east of Winchester by the Romans) and valley gravels, which would have provided a good foundation, were covered by a layer of peat from the decaying vegetation of the river valley, then chalky marl washed down from the town’s western slopes.

The situation was summarised by Sir Thomas Jackson, the architect who oversaw the repairs (although recent archaeological research has shown that in fact the foundations were more sophisticated than Jackson believed): ‘Bishop Walkelin’s men dug down to water and then seem to have scooped out the marly soil overlying the peat, and part of the peat itself, in some cases within a foot or so of the hard gravel on which we underpin. Into these excavations they pitched loose flints and chalk till they were able to build in the dry.’ The Norman builders resorted to driving in oak piles below water table level in an attempt to provide firmer foundations.

When the east end of the Cathedral was extended in the 13th century, forming the Retrochoir, the builders were faced with even worse problems, as the underlying gravel was well below the water-table. They laid a double layer of beech logs in the trenches, but the peat layer here was over five feet deep, and would be compressed by the weight of the building.

Numerous newspapers and periodicals carried extensive reports of the risk to the Cathedral, and of the progress of the work, and many included diagrams to explain the geological problem, such as this example from the Illustrated London News, 28th November 1908 (Winchester Cathedral Archive: Hampshire Record Office: DC/E3/6/4/9).

There is evidence that before the end of the medieval period the building was already sinking, and the Cathedral’s first architectural surveyor, William Garbett, appointed in 1809, warned of ‘alarming fissures’ in the South Transept. In the annual report of the Architect to the Dean and Chapter in January 1905, the Winchester-based John Colson, attention was drawn afresh to the serious problems; he commented on the foundations being on alluvial soil, ‘charged with water, which ebbed and flowed with the seasons’. The Diocesan Architect T G Jackson made a first inspection in March 1905, and on his advice the consulting engineer Francis Fox, who had extensive experience of foundations and water problems, was called in. Photographs preserved in the Cathedral Archive show the dramatic nature of many of the cracks which had opened in the building.

Photographs of cracks in the North Transept, from an album presented to the architect Sir Thomas Jackson by the contractor Mr Thompson (Winchester Cathedral Archive: Hampshire Record Office: DC/E3/6/4/12).

Fox recommended the shoring-up of the worst-affected area, and the consolidation of the crumbling walls by pumping cement grout into the core of the walls. Once this had been done, it would be possible to underpin them by laying concrete foundations and building up to the existing footings.

Photographs of the shoring-up of the south-east part of the Cathedral (Winchester Cathedral Archive: Hampshire Record Office: DC/E3/6/4/12).

However, there was a problem: when the peat layer was breached, the excavations were flooded with water, up to 13 feet in depth; pumping proved only partially effective, and the use of the pump threatened to cause further subsidence. In a report dated 30th March 1906, Fox therefore suggested ‘A diver could… remove the remainder of the peat, and place in position the bags of concrete’.

Extract from Francis Fox’s report suggesting the role that could be played by a diver, included in a volume of reports, specifications etc presented to the Cathedral by Sir Thomas Jackson (Winchester Cathedral Archive: Hampshire Record Office: DC/E3/6/1/3).

Siebe Gorman and Co, who were said to employ about 200 divers, sent two of their most experienced men: William Walker and his colleague named Rayfield. Walker was born in 1864 and trained at Portsmouth Dockyard in the late 1880s, joining Siebe Gorman in 1892; he had worked on projects ranging from the Gibraltar dockyard to Victoria Docks in London. The divers arrived in April 1906, and initially shared the work between them, but after the first year Walker undertook the whole work until its completion in September 1911.

Walker worked for two four-hour shifts each weekday, spending about six hours under water each day. Over the course of five and a half years he would lay some 26,000 bags of concrete below the Cathedral. In 1906 a journalist on the Morning Leader described having ‘walked the plank into one of these black caverns underneath the walls of the Cathedral’. Under eleven feet of water, Walker ‘was shovelling a slimy mixture of rotten wood, peat and chalk into buckets to clear one of the 9ft. square spaces from which the water will be pumped, and in which a solid support will be built. By the aid of a match one could see the foundations of the Cathedral shored above his head with beams, like the passage of a coal mine.’

William Walker was one of a large number of people working on the restoration project, but it is not surprising that the magnitude of his task caught the public imagination, and that he was featured on postcards at the time, such as this one by the Winchester photographer C E S Beloe.

Hampshire Record Office: HPP5/1/31.

Nonetheless, we should also remember the others who worked on the project above ground, some 150, many of them being employees of the contractors John Thompson of Peterborough.

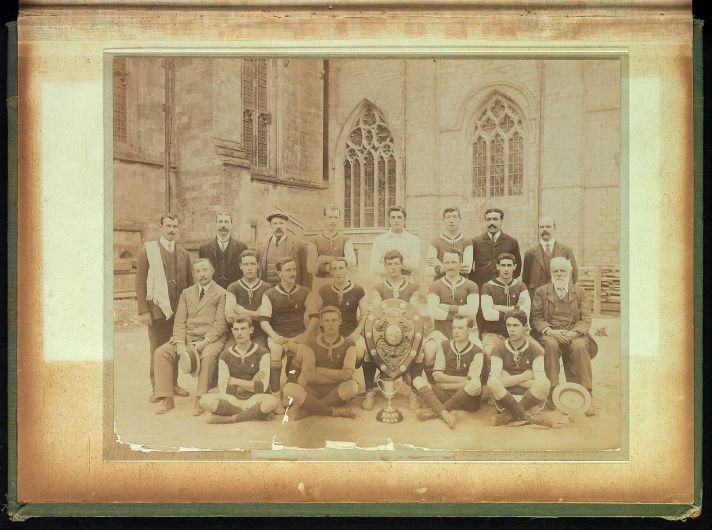

Photograph of Messrs Thompson’s football team and supporters; William Walker is shown third from the left in the back row (Winchester Cathedral Archive: Hampshire Record Office: DC/E3/6/4/5).

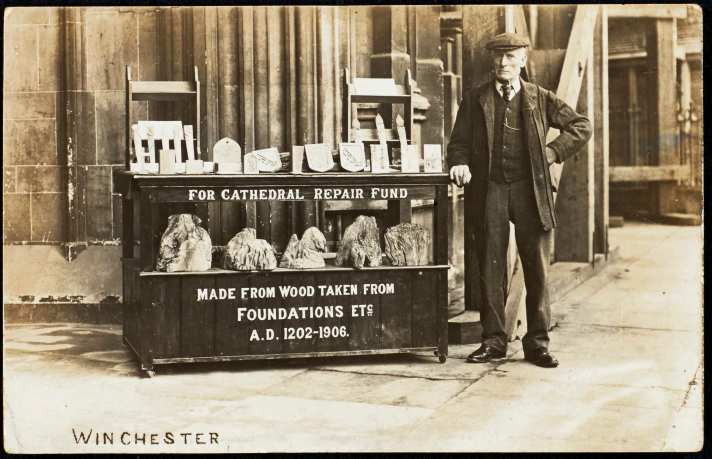

Also important was the work of those who helped to make possible its completion through fundraising: a number of innovative schemes were devised to help the repair fund, including selling wooden souvenirs, ranging from crosses to breadboards, made by the Laverty family of carpenters in Winchester from beech blocks removed from the Retrochoir foundations, and the Winchester National Pageant staged in 1908.

Postcard of the Cathedral Repair Fund souvenir stall (Hampshire Record Office: TOP343/2/405)

Having survived the dangers of working in the darkness below the Cathedral, William Walker died on 30th October 1918 aged 54, a victim of the influenza pandemic. He was buried in Beckenham Cemetery, and in March 2018 a commemorative plaque was unveiled by the Dean of Winchester Cathedral, the Very Revd Catherine Ogle, on the house where he had lived in Portland Road, South Norwood.

Much more detail about the work of William Walker and many others to rescue the Cathedral between 1905 and 1912 can be found in The Winchester Diver: The Saving of a Great Cathedral by Ian T Henderson and John Crook (Henderson and Stirk, 1984), a copy of which is available at the Record Office, and from which much of the information in this article is taken (Dewey classification 726.609422735). The story is told more briefly in William Walker: the Diver who Saved Winchester Cathedral by Canon Frederick Bussby (revised by John Crook, 2005).

In the Cathedral today you can still see signs of the cracking of the masonry which caused so much concern in 1905, as well as other clues to the story of the restoration; you can read more about what can still be see today in a recent article by David Farthing in the Record Extra series published online by the Friends of Winchester Cathedral, at www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Safe-Sound-and-Secure.pdf or via the relevant link from www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/join-us/become-a-friend/record-extra. The story has now been re-told for children in Diver Bill: The Man Who Saved Winchester Cathedral by Judith Anderson, illustrated by the Winchester artist Tony Kenyon.

The centenary of William Walker’s death is being commemorated in a display in the Cathedral, until the end of October, including some souvenirs carved from wood removed by him from beneath the Cathedral, two objects owned by him, a few items from the archive, and some of Tony Kenyon’s artwork; please see www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/events/william-walker-100-exhibition for more details. Over the weekend of 6th-7th October, there will be special tours and a commemorative Evensong (on Saturday) and a family trail and craft activity (on Sunday); more details are available at www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/events/william-walker-100-celebrations.

All are welcome to visit Hampshire Record Office to see the albums, notebooks and other items relating to the Cathedral restoration of 1905-12, which are available for consultation (mainly in digital form, to save handling the originals) as part of our normal search room service. You can see a listing of the documents relating to the restoration by going to our online catalogue at http://calm.hants.gov.uk/advanced.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog and simply entering the reference DC/E3/6 in the finding number box; most relevant material has been catalogued under this reference, except that architectural drawings relating to the restoration have been catalogued under the reference DC/E8/2.

David Rymill, Archivist.

I have just inherited a bread board from the foundations of Winchester Cathedral that was sold to my grandfather, it has the emblems carved into it.

LikeLike